For banks and other financial institutions one of the key challenges of GDPR will be how to implement the right to erasure (a.k.a. the right to be forgotten).

This not only requires institutions to manage and control the purpose and consent of processing personal data for every individual, but it also contains provisions specifically referencing other regulations, which may overrule the right to be forgotten.

The main regulatory drivers of personal data retention are in codes of commercial law, yet there are many other exemptions which overrule the right to be forgotten, at least for a defined period. Both MiFID and MAR, for example, contain requirements to report and retain personal data of employees – something that HR and Compliance executives will need to factor into employment contracts and their procedures around retention.

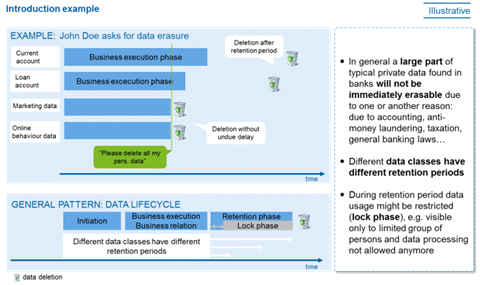

However, for banks the key focus will be the proliferation of client data within their systems’ architecture. To illustrate this challenge, the figure below uses a simple example of a customer, “John Doe”, with several active bank accounts who has asked for erasure of his personal data:

Figure 1: Introduction example “John Doe asks for data erasure”

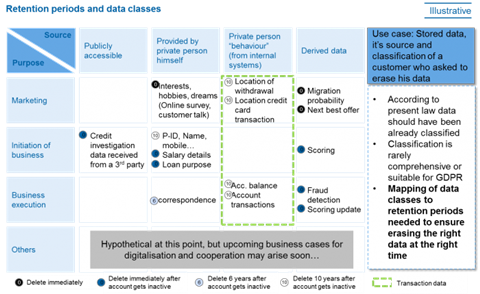

This example shows that a simple classification of data as belonging to a “current account” or “marketing data” is not sufficient to decide whether the data can be erased immediately or not, because there might be an overlap. Transactional data on the current account might be used to analyse the behaviour of John Doe and thus (in combination with other data) drive individual marketing offers, as highlighted in green in the next figure:

Figure 2: Classification of data and related retention periods

In this example, the location of a withdrawal or credit card transaction is used for marketing purposes. In parallel, it is crucial for a financial institution to keep this information for the length of the retention period to be able to prove the integrity of its balance sheet and processed transactions. Furthermore, this information may be needed for other purposes such as anti-money laundering, fraud detection etc. As a result, processing of the personal data for the purpose of marketing is no longer allowed as the customer has revoked his consent and asked for data erasure; however, the data itself may not be immediately erased due to other obligations or longer retention periods.

The example shows that GDPR requires institutions to have a much deeper understanding of the purpose for which personal data is kept. In order to do this, each information item will need to be classified not only with the purpose, but also the source from which a bank has collected it. These data classes then need to be mapped to the applicable law and related retention phases.

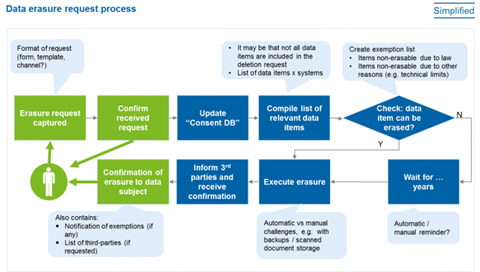

We finalise this short example by outlining a high level data erasure process in the following figure:

Figure 3: H/L data erasure process

To implement an effective data erasure process institutions need a comprehensive end-to-end view of all processes and systems dealing with personal data, while keeping in mind that this regulation is not only another regulation to deal with, but also a customer interaction.

In order to optimise the customer experience, institutions will need to implement appropriate channels to capture requests and to keep the customer informed, especially about which data has been deleted and any exceptions. At the same time, details of customer requests need to be managed, the relevant data items and their location need to be made transparent and checks on whether the data can be erased or not need to be performed – all before any data can be erased.

Where exemption rules are identified, erasure of data will be delayed. Where third parties are involved, they must be informed of the erasure request and confirmation needs to be provided by them as well. Each of these execution steps can be very time consuming and cause significant manual effort if the institution does not have sufficient tools in place to support the process.

Indeed, for most financial institutions, an “ideal” supporting tool will be not in place before May 2018, so manual processes will have to be implemented. Looking ahead, one would expect new systems (either third party or internally designed) to provide APIs to support data erasure.

The more challenging part seems to be the collection (and maintenance) of all the metadata needed to compile the list of relevant data items affected in combination with the exemptions. To do so, a comprehensive view of all data belonging to individuals (e.g. as part of an extended business glossary per BCBS239), as well as the data location and its purpose, needs to be in place. Furthermore, information on whether individuals have given or revoked their consent to process and keep data needs to be connected to this.

Conclusion

GDPR clearly has the potential to keep financial institutions busy for a while – not only to be compliant by May 2018, but also to fully optimise their solutions to a mature and efficient level. Data erasure will require several options and decisions to be made with full consideration of the costs and benefits within the existing IT architecture.

Given the May 2018 enforcement date, we can assume that the eventual target set will be not reached for all systems and processes. We therefore strongly advise financial institutions to implement their tactical response to GDPR with the roadmap for future development of the organisation and IT-landscape in mind. This approach particularly holds true for the right to erasure, which in the short term may only require a defined and tested manual process that is transparent, replicable and efficient.

By Dan Crow, Principal, zeb consulting

No comments yet